On New Year’s Day 2016, a 17-year-old West Allis girl returned home at 5 a.m. after a night of heavy drinking.

Less than 24 hours later, her father found her in bed, dead from an overdose of the narcotic painkiller methadone.

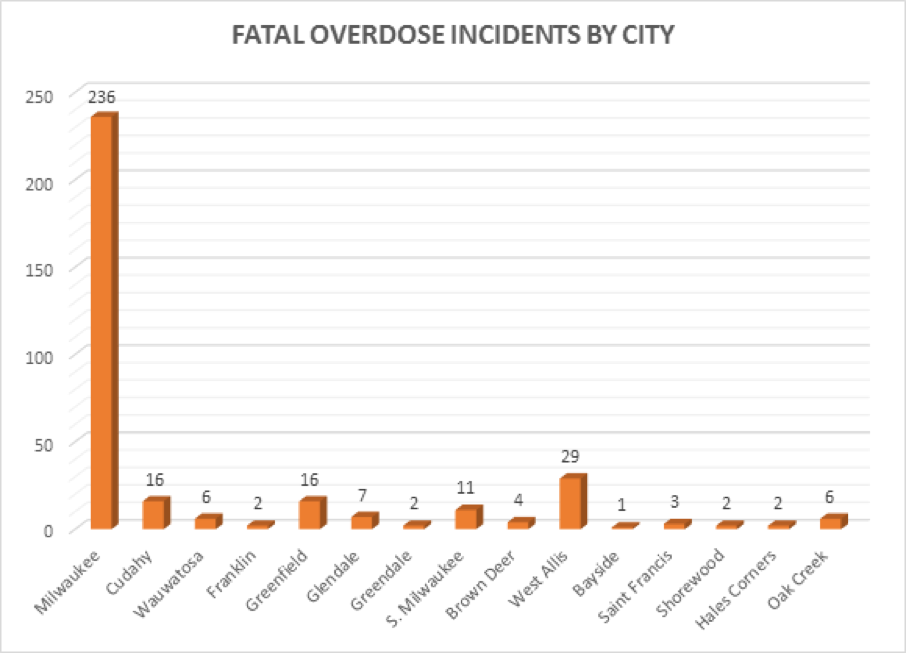

By the time 2016 ended, 343 people died from drug overdoses — more than from car accidents and homicides combined and more than three times the total in 2002.

Among the dead were three 1-year-olds, one who died of a methadone overdose, and two from the narcotic painkiller oxycodone. A 93-year-old woman died from a combination of methadone and the prescription sedative temazepam, which treats insomnia.

In 2002, when 109 people died from drug overdoses, the oldest was 62; the youngest, 15.

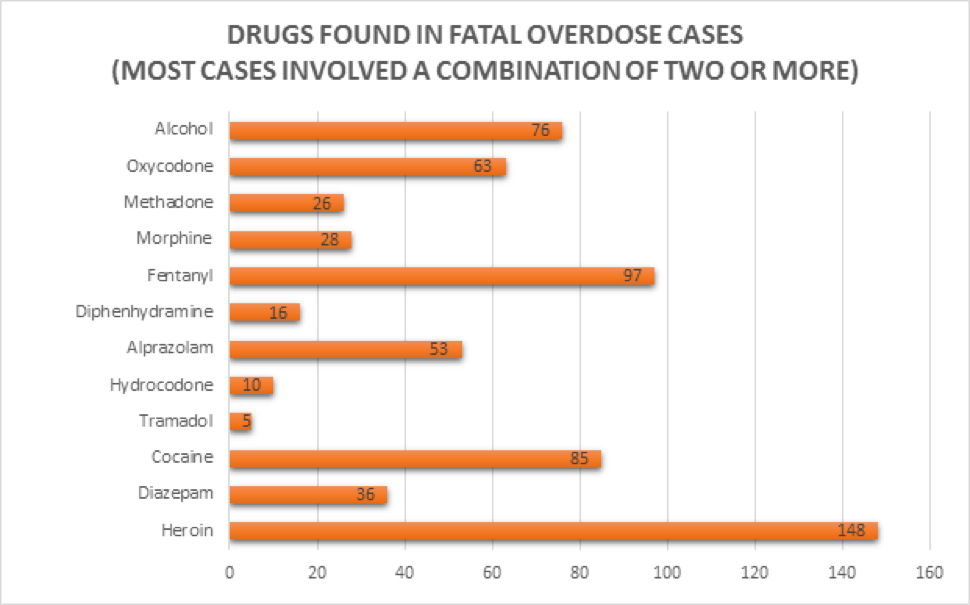

In 2016, three drugs turned up over and over again in toxicology tests: heroin was found in 148 cases; cocaine in 85; and fentanyl, a powerful and often illegally made opioid, in 97 cases.

Alcohol was a part of the deadly mix in 76 instances.

With brand names such as Xanax and Valium, anti-anxiety drugs known as benzodiazepines showed up in 99 cases. Both alcohol and benzodiazepines suppress the central nervous system, and if taken in large enough amounts or with opioids, can cause a person to stop breathing.

“Basically, none of us saw this coming, both in terms of volume and the new drugs involved,” said Chief Medical Examiner Brian Peterson.

The deaths occurred in apartments and homes, on the street and in hospitals in almost every neighborhood in the county.

They happened on a Milwaukee County bus on the South Side; on the sidewalk in front of a Kopp’s Frozen Custard in Greenfield; in a gas station bathroom on the Northwest Side; and in a basement storage unit of a West Allis apartment complex.

A 20-year-old man, his body still warm, was found in the driver’s seat of his car in the parking lot of a McDonald’s on Milwaukee’s Northwest Side. He apparently passed out so quickly after taking fentanyl and a tranquilizer, that his McDonald’s bag and a soda still were in his lap and his keys were in his right hand.

Only three more affluent communities – Whitefish Bay, Fox Point and River Hills – did not log an overdose death in 2016.

Most of the county’s overdoses were caused by opioids mixed with other drugs.

Years ago, the deaths mostly involved cocaine and heroin, Peterson said. Then, in 1995, the painkiller Oxycontin arrived on the scene, sparking an epidemic of prescription painkiller abuse.

Today, fentanyl, much of which is made illegally and is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, is the cause of many of the deaths. The drug often is mixed in with heroin, sometimes without the user’s knowledge.

Arif James Weiss, 26, had a history of prescription painkiller and heroin abuse, but it was fentanyl that killed him on Sept. 4 last year in his Wisconsin Ave. apartment.

AJ, as he was known, thought he was taking heroin, said his mother, Holly Nerone. But the medical examiner determined it was fentanyl.

“They can throw whatever the hell they want in these drugs to try and hook people or give them a better high,” his mother said. “It’s almost impossible to ever bring someone to justice for it.”

Fifteen years ago, in 2002, fentanyl was just starting to show up in toxicology tests. It was found in only 3 of the 109 overdose deaths that year, according to medical examiner’s records.

Before the emergence of fentanyl, heroin use surged, both nationally and in Milwaukee County.

A study this month in the journal JAMA Psychiatry, found a big increase in heroin use between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013.

Data from Milwaukee County mirrors that trend. Deaths involving heroin increased from 15 percent of all drug deaths in 2002 to 43 percent in 2016.

During that 14-year period, when deaths from all drugs more than tripled, heroin and fentanyl led the way.

While the bodies go to the Medical Examiner’s office, the Milwaukee Fire Department attends to both the dead and the near-dead. Last year, paramedics administered the life-saving, opioid overdose drug, Narcan, to more than 1,000 people.

“We go on an overdose every day,” said Lt. Aaron Kriel, a paramedic with MED-7, the busiest paramedic unit in Milwaukee.

Nearly a third of all deaths investigated by the Medical Examiner’s office involved drugs in

2016.

Milwaukee County has one of the few Medical Examiner offices in Wisconsin that has a toxicology center in the same building. From blood, vitreous fluid in the eye, and other organ samples, a toxicologist can determine what drugs were taken and if alcohol was involved.

Why is this happening?

Peterson says it’s a collision of several factors: over-prescription of opioids, regulations emphasizing more pain control to make patients happy and the rise of illegal and cheap fentanyl.

This story was done using a Medical Examiner’s database of the 343 drug overdose cases in 2016. A similar database from 2002 also was analyzed.

Of the 343 overdoses, 58 were pronounced dead at a hospital, with the majority ending up at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center on W. Oklahoma Ave. and S. 27th St.

In about 80 percent of the cases, the user never made it a hospital.

Many of the victims were from middle class or poorer areas with 31% of the cases occurring in Milwaukee County suburbs.

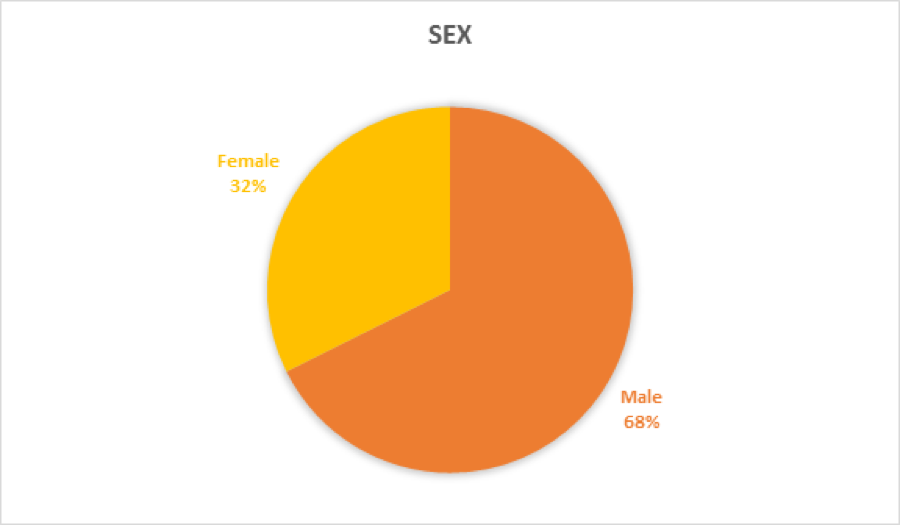

Sixty-eight percent of the victims were male, and 68 percent were white.

Sixty-three percent of the cases (216) were mixed-drug intoxication, meaning two or more drugs were found in the body of the deceased. Alcohol is counted as a drug when it’s involved in an overdose death. It played a deadly role in 76 of the cases. Heroin was involved in 43 percent of the cases.

“I have cases with four, five, six different drugs,” said deputy medical examiner Wieslawa Tlomak.

Enlarge

Fentanyl, which was involved in 28 percent of deaths, is cheap to produce and many times more powerful than heroin. If the user doesn’t know that, he or she may get an opioid dose that is much stronger and more deadly than what they expected.

In 2002, the drug only was found in three deaths, less than 3 percent of the total.

Two of the drugs involved in last year’s overdose deaths — methadone and buprenorphine — also are used to treat opioid addiction.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman took cocaine – a stimulant- fentanyl and heroin, both depressants, and then added alcohol to the mix.

In another, a 34-year-old Greenfield mother of four died of a combination of oxycodone, amphetamine and benzodiazepine. She was revived by paramedics in the field and taken to St. Luke’s Medical Center where her heart stopped again. She again was resuscitated, but died at the hospital.

Paramedics are trying to fight the “opioid tsunami” with the prescription antidote Narcan (naloxone).

Narcan can be requested by users from their doctor or from several community health organizations in the city.

But it doesn’t always work.

On March 2 last year, a 36-year-old man was passed out on a county bus. He had labored breathing when firefighters arrived, so they administered Narcan as a nasal spray, but he could not be resuscitated. He died of a fentanyl overdose.

And sometimes users just don’t want it because it interferes with the euphoric effect of the opioid they took.

“They are very angry at us for taking away their high,” said Deputy Chief Steven Riegg.

Even more Narcan may be needed this year. Overdose deaths are on pace to exceed last year’s record, said Karen Domagalski, operations manager at the Medical Examiner’s office.

As of May 11, the county was on pace for 390 deaths, she said.

This story was written by Jordan Garcia, with contributions from Brandon Anderegg, Jenna Gaidosh, Dwayne Lee, Christina Luick, and Amanda Watter.